Lynne Tatlock is the Hortense and Tobias Lewin Distinguished Professor in the Humanities and director of the Comparative Literature program. Kurt Beals is associate professor of German and comparative literature.

September 2–4, 2021

Transnational Framings: The German Literary Field in the Age of Nationalism, 1848-1919

Thursday, September 2

Virtual exhibition and reading

Friday, September 3

Panel 1: Re-Drawing Borders

Panel 2: Publishing Contexts

Saturday, September 4

Panel 3: Reframing Politics and Reception

Panel 4: Nation and World

See website for Zoom registration; those affiliated with WashU may attend in person

How are national identities defined within, and against, international contexts? What does it mean to speak of a “national” literary tradition, particularly when political borders are shifting, and when the language and literature in question straddle those borders? How do international and transnational influences, such as translations from abroad, impact the development of a national literary tradition? The symposium “Transnational Framings: The German Literary Field in the Age of Nationalism, 1848-1919” considers these and related questions, focusing on German-language literature and culture but considering them in relation to transnational and international cultural forces.

Consider an example of trans-Atlantic cultural exchange: The Columbian World Exposition of 1893 in Chicago provided the occasion for national display of goods and products in an international context. While the displays could be a source of national pride in the historical moment, hindsight brings sharply into view the international dynamic in which such national pride flourished and the reductiveness and ironies of such national self-representation per se. Imperial Germany proudly claimed considerable space at the fair with, among other things, a display of 300 books by women in the Woman’s Building. A closer look at these books by women in 2021 reveals that they did not necessarily include those that Germans were actually reading, that they represent contradictory points of view, and that few of them have stood the test of time. Besides, given the separation of the Woman’s Building from the rest of the fair, it is not entirely clear that literature by women was an integral element of national self-conception to begin with. Beyond the fairgrounds and back home in Europe, cultural production and political debate in Germany and Austria were taking many twists and turns — in part nationalist-flavored, in part cosmopolitan, and always already shaped to some degree by international contexts.

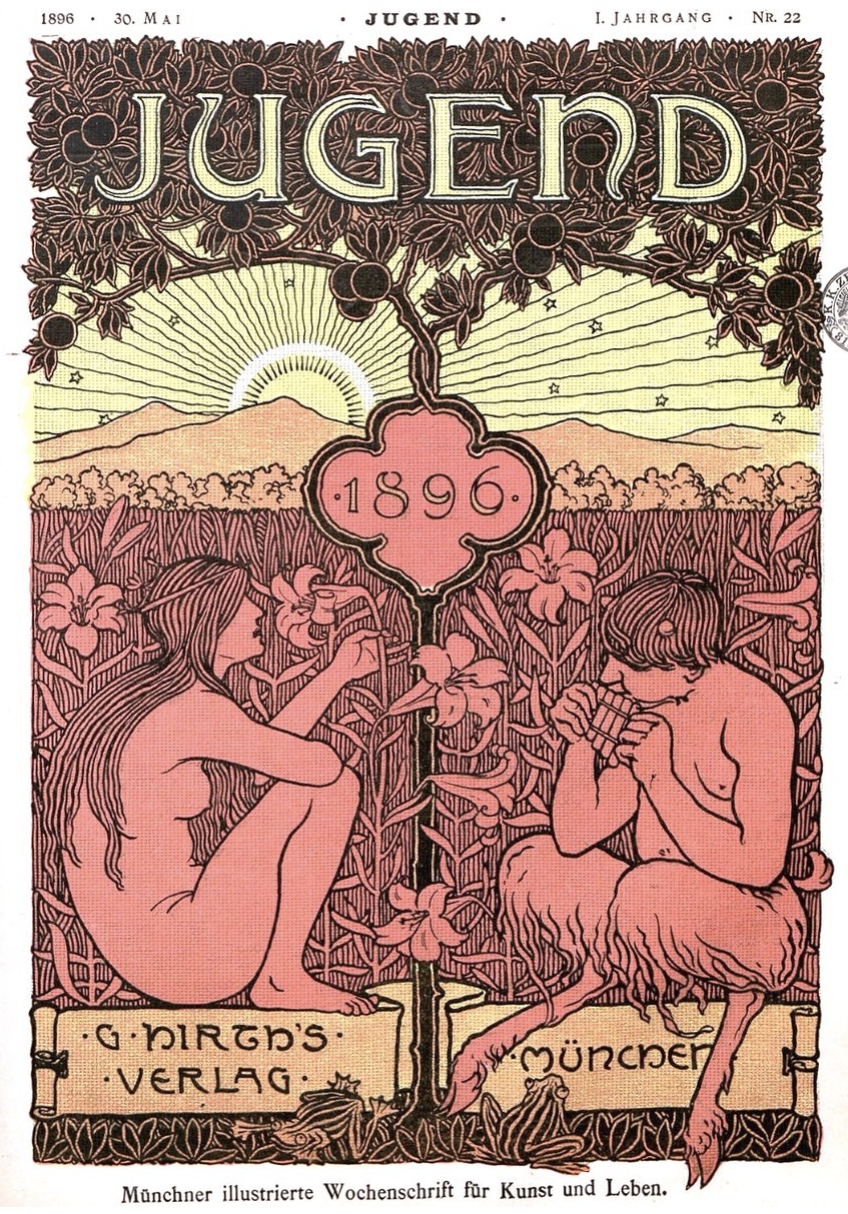

The establishment of the German Empire in 1871 upon the defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War and the unification of 27 sovereign entities with the exclusion of Austria provided the occasion for jingoistic attempts to present unified national self-representations but also occasioned the first efforts toward international peace movements. As is especially pertinent to our symposium, narrowly focused national histories of German literature proliferated, intended not just for experts but also for more popular consumption, often in elaborate formats for the purpose of ostentatious display within the home. Even as these histories focused tightly on select national cultural milestones, reading and book consumption went its own way, imitating international styles in book formats; offering German translations of, especially, French, English, American, Scandinavian, and Russian literature; and seeking to participate in international modernist trends. Some publishers tried to have it both ways. The Oldenbourg publishing house in Munich, for example, simultaneously published anthologies of German short stories and collections of translated short stories originally written in other European languages. Meanwhile German-speaking Austria — now politically separate from greater Germany and positioned as a multinational and multilingual empire — constructed its own idea of German literature even as many of its leading German writers published regularly with publishing houses within the national boundaries of Imperial Germany.

“Transnational Framings” focuses on a particular era in German history (1848–1919), which has been conveniently labeled in modern literary histories as the Age of Nationalism, even though it should by now be well understood that neither Austria nor Germany was internally culturally coherent, that multiple ideas of “national” co-existed, and that countervailing currents gained some traction in the period. This symposium features presentations by 15 leading German studies scholars — including Washington University faculty as well as colleagues from the United States, Germany, and Austria — that explore the possibility of setting aside this siloed national framing of German literary and cultural history and considering instead the transnational connections, rivalries, politics, and trends that shaped cultural and literary production and indeed what books people living within the newly redrawn political boundaries of Germany and Austria actually read. While by no means denying the nationalist impulses of the era, the case studies presented here attempt to present a more complex picture, one that uncovers transnational dynamics, multiple ideas of nation, and the role of literary and cultural production and consumption in this volatile historical setting.

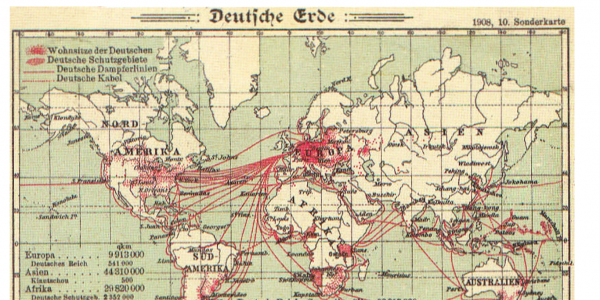

Headline image: The map “Deutsche Erde” (German earth) illustrates routes related to emigration and colonization and, Lynne Tatlock says, suggests the bigger world that at least some Germans might have been thinking about during the 19th and early 20th centuries.